Maritime Drug Interception

CTF 150

Hashish, heroin and methamphetamine. Every year, in an area of the Indian Ocean covering 3.2 million square kilometres, dhows stacked with illicit cargo attempt to reach their buyers. And every year, Combined Task Force 150 (CTF 150) takes them on.

08 September, 2025

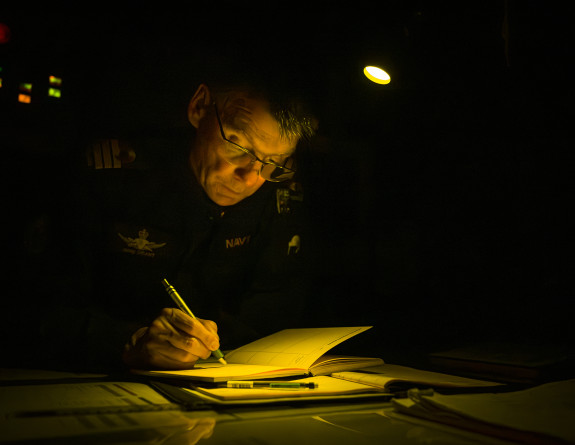

It’s 0745 in Bahrain and already there’s an expectation of a 50-degree day. Inside CTF 150’s air-conditioned headquarters building in Naval Support Activity (NSA) 1 Captain Dave Barr RNZN, Chief of Staff for CTF 150, nods to the briefer to start the morning update brief to Commodore Rodger Ward, the Commander of CTF 150.

There’s plenty to talk about. Fourteen New Zealand Defence Force personnel, plus foreign personnel from six other nations provide Commodore Ward and Captain Barr with a snapshot of the last 24 hours and what is likely to happen in the next 24. The team have a list of known or suspected drug smugglers, where they could be, and if they’re likely to be loaded up or unloaded. There’s a contact of interest (COI) that needs to be explored further if a maritime asset – a coast guard vessel or warship – can be directed to intercept.

This year, for the second time in the Task Force’s 23-year history, New Zealand is in command, partnering with India in the Deputy Commander position.

CTF 150 is part of the Combined Maritime Forces coalition, a 46-nation maritime partnership set up to promote security and stability in the maritime areas of the Middle East, including the Indian Ocean, Northern Arabian Sea, Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. CTF 150, one of five task forces, is dedicated to counter-narcotics in the Indian Ocean and Northern Arabian Sea, The Persian Gulf and Red Sea are covered by other CTFs.

The names for the known drug routes by sea are colourful for what is really a dark business – the ‘hash highway’ (hashish) to Yemen; the ‘smack track’ (heroin) to Tanzania and Mozambique; the ‘crystal causeway’ (meth) towards the Pacific, Australia and New Zealand. The returns, which run into the billions, fund terrorist and organised crime groups.

Boarding Operations - Combined Task Force 150

Captain Barr notes the weather report, which indicates favourable sea conditions in their area of interest. Drug running across the high seas is seasonal, and no ship’s master, illicit cargo or not, likes the monsoon season. It’s the reason why the team is in place now.

The contact of interest looks worth investigating. In previous years CTF 150 has made use of airborne surveillance or even Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles, but in the end it comes down a hands-on approach – interception and boarding – if an asset is available. In theory, both Commodore Ward and Captain Barr have a lot of maritime assets at their disposal. But on any given day, the hard realities of the Middle East can cause priorities to move.

“There’s ships and aircraft in abundance, but everyone wants them for something,” says Captain Barr. “So what is the priority? The issue is that Combined Maritime Force is not a ‘state-facing’ organisation, which means it doesn’t do anything against countries. It’s looking at drugs and piracy and the non-state actors (the criminal and terrorist networks) that move them. But the assets we need come from nations that might have competing national interests at stake in the region, which takes away their promised asset to do something else.”

The team at CTF 150 could be told: you can have those assets for two weeks – but it could get pulled. Or, we’re on the way to Mumbai, but we can do this while we’re in the vicinity.

“’I’m going from A to B. If you need me, I might be able to help.’” It’s the difference between ‘direct support’ and ‘associated support’,” says Captain Barr. In theory, an entire carrier strike group could provide ‘associated support’. But in practice, a carrier group tends to remain nationally-tasked to the nation’s interest.

But this year CTF 150 has a direct support asset – the Royal New Zealand Navy frigate

HMNZS Te Kaha is our Royal New Zealand Navy's first Anzac Class frigate. Te Kaha is a purpose-built warship constructed to the German MEKO 200 design.

Build up to boarding

Commander Andy Grant, Executive Officer of Te Kaha, likens boarding operations to a “slow drumbeat, building to a crescendo”. On board Te Kaha, the specialists have been working with the CTF staff in Bahrain to build a picture of likely targets.

“It’s not a photo-realistic picture, it’s more like abstract art. It’s made up of reports, sometimes actual imagery and perhaps a bit of history on how things have fitted together before. It all goes towards creating a valid target for boarding.”

For the latest Contact of Interest, the jigsaw puzzle of intelligence is collectively viewed by the ship’s Command Team, with ensuing discussions and views among the Principal Warfare Officers on what it all actually means. The Commanding Officer, Commander Fiona Jameson, listens intently, weighs the evidence and legal criteria and makes a decision.

“Make the Pipe – Five minutes to Command Boarding Brief.”

The key players gather in the ship’s darkened Operations Room, forming a tight semi-circle around the Commanding Officer’s chair. There’s some chatter but it’s subdued; discipline keeps the anticipation focused and professional. There’s excitement there too – the ship is transitioning from searching to interception.

The on-watch Principal Warfare Officer steps through the checklist and confirms everyone has their part of the brief prepared and ready. Everyone comes to attention as Commander Jameson takes her chair. The brief is well practised and familiar. It covers all aspects of the boarding, identifies new risks and provides the opportunity for questions and clarifications. Commander Jameson concludes the briefing with a simple statement:

“Boarding as briefed, is approved.”

The legal side

Back in Bahrain, Captain Barr ponders the legalities that make boarding a vessel on the high seas possible. CTF 150 operates under Article 110 of the 1982 United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which allows a warship to board a suspicious vessel, in accordance with Article 108 Illicit traffic in narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances and Article 17 of the 1988 United Nations Convention against Illicit Drug Trafficking in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances: Illicit Traffic by Sea.

But that long piece of legalese is dependent on one thing: is the vessel of interest sailing under a legitimate flag, or is it stateless?

“Our warship has to request to CMF in order to conduct a Flag Verification Boarding (FVB),” says Captain Barr. “When approved, that means a boarding team goes over to the vessel and informs the ship’s master that they intend to come aboard. They’ll do a security sweep for safety and check the vessel’s paperwork. If it doesn’t have the requisite paperwork, including port of registry, the Commanding Officer of the warship can declare the vessel is stateless. We will then concur, if satisfied, through the CMF legal chain, and allow the warship to continue its operations.”

If the vessel is sailing under a legitimate flag, the warship’s boarding party could be clambering over bags and bags of drugs to prove that legitimacy, but yet have no legal right to be there, and have to get off. But with this contact of interest, it’s not the case. Te Kaha is free to impose its domestic jurisdiction on the suspect boat and undertake a search.

Call to action

“Hands to Boarding Stations… Hands to Boarding Stations… Hands to Boarding Stations…”

On board Te Kaha, four main areas swing into action. The Boarding Team, mustered in a space where all their equipment is stored, put on their body armour, life jackets and ancillary kit. Weapons and ammunition are issued. A final brief is delivered before they move to the embarkation point.

The Evolution Team prepare the ship’s RHIBs for launching. The coxswains, who attended the Operations Room brief, have a good idea of the plan. Their bowmen are armed with a

The MARS-L is the primary individual weapon for all three Services and is used by every soldier, sailor and airman within the NZDF. It is available in two different primary configurations depending upon the individual Service requirement Our Defence Force has eight SH-2G(I) Seasprite maritime helicopters, operated by No. 6 Squadron. They are flown by Royal New Zealand Navy aircrew and maintained by Royal New Zealand Air Force maintainers.

The Aviation Team, on the flight deck, run through their well-drilled process to get the helicopter with its weapons loaded and ready. Its job is to provide an overwatch, with the helicopter’s loadmaster manning a

The MAG 58 is used in a variety of configurations across the NZDF to provide offensive and defensive support. It can be fired off its own integral bipod, a sustained fire tripod or various vehicle and aircraft mounts.

Smugglers can resort to extreme measures. During New Zealand’s last CTF 150 command in 2022, American patrol ship USS Sirocco was closing on a dhow when it became apparent the crew were preparing to scuttle it. A large explosion followed, with many of the dhow’s crew blasted into the sea. The Navy rescued the survivors, some severely injured, and recovered a large quantity of narcotics before the vessel sank.

These situations are rare, but it demonstrates the risks faced by boarding party, and the risks dhow crews are prepared to take sometimes. The helicopter launches and flies ahead to establish ‘eyes on’ the target. The Boarding Team are embarked in the two

Our Juliet 3 (J3) RHIBs are carried as embarked seaboats on all Navy vessels (usually two to a vessel), and utilised within a land-based boat squadron at Devonport Naval Base.

“Go go go!” is passed and the RHIBs speed ahead to make their final approach to the target vessel – hailing the crew on deck while getting their jumping ladder ready. It’s a Jelibut dhow, about 30 metres long. Five crew on deck have their hands raised above their heads. The ship establishes an overwatch position, circling the target vessel at a few 100 metres.

With the boarding team onboard there is a pause as they conduct their drills, After 12 long minutes, they declare the boarding as ‘Low Threat’. One of the RHIBs returns to Te Kaha and is returned to its cradle on the upper deck. In the Operations Room, the team remain patient and keep watch on the screens as information is drip-fed back from the dhow. They can see the Boarding Team searching the upper deck but can only rely on radio reports as the search goes below decks.

It takes about eight hours, with the team on board changing out as the day goes on.

Finally, the search is complete; no drugs found. The teams are recovered back to Te Kaha.

“This is the reality of real-world ops,” says Commander Grant. “It can develop into a fairly mundane grind. Learning to deal with that, without becoming complacent and dropping the ball is hard, and you can’t really train for it. It is real on-the-job training - and developing a collective professional stoicism.”

Winding down

In Bahrain, the excitement eases as the reports come in.

“It is quite a change in atmosphere when we go to launch,” says Captain Barr. “When we receive that request for boarding, the chatter builds, there’s lots of communication and getting actions approved. It’s a bit of an event atmosphere, and everyone gets involved.”

Not for the first time, Captain Barr reflects on how well the team have performed – a happy situation for a Chief of Staff.

“One of the best things for me about this deployment is the staff and seeing this team own the mission. They’ve made it theirs, to such a high standard that the Boss and I let them run it their way – because it works! We’ve seen them develop into professionals, doing a phenomenal job. Everyone supports each other and covers for each other without me getting involved. It allowed me to focus on working with our partners in the 46-nation coalition to best support the mission and ensure both mission success. It's been a rewarding, enabling environment for our staff to learn, develop and come back to New Zealand with bucket-loads of experience.”

The non-result is hardly a dent for the team; under New Zealand’s command CTF 150 has had some spectacular hits this season. In a particularly notable bust, Royal Navy frigate HMS Lancaster seized 1,000kg of heroin, 660kg of hashish and 6kg of amphetamine, totalling a street value of NZ$1billion.

These interceptions and seizures are all ‘catch and release’. Once the narcotics are seized the dhow and the crew are free to go on their way. The drugs are then disposed of. Captain Barr says before they destroy the drugs, they’ll take a tiny sample for later analysis, as part of building a database of where drugs originate from.

“The boarding party gives the master a receipt. It’s not anything like you get from an EFTPOS machine, it’s just a piece of paper that says, on this day and this time, we came aboard.” The procedure, part of the formality of boarding a vessel and removing items, is also proof for a ship’s master that the drug loss was outside their control when they go back to their port of origin.

$1.8 Billion

Street value siezed under New Zealand’s command

The home and away game

In all, CTF-led boardings this season resulted in the seizure and destruction of seven tonnes of narcotics, with a combined street value of more than $NZ1.8 billion. Overall, maritime assets – direct and associated – carried out 55 boardings. The value of having a direct support asset like Te Kaha was enormous, with the ship conducting a boarding within only 36 hours of coming on task into the region.

But it’s been down on other years. New Zealand’s last stint, in 2022, was the second most successful command in the history of the Combined Maritime Forces, with $NZ3.05 billion worth of drugs seized.

“With our effects campaign and media releases, it’s possible the smugglers knew we had ships out there, and I reckon we had a big influence with Te Kaha there in direct support,” says Captain Barr, “It’s not just about the awesome pictures of bags of drugs on a flight deck after a successful interdiction, but it’s also about disruption and deterrence – and I think we achieved that.

“I think they had to change their plans. We were doing more boardings, we were deterring the smugglers and pushing them closer into shore, because we were seeing more domestic coast guard authorities doing boardings.”

The effect New Zealand has achieved is undeniable, but some might say it’s going a long way outside our usual territory – especially for a frigate. The last time a RNZN frigate was deployed to the Middle East was in 2015.

55

CTF-led boardings this season

“We have a national interest in sending a frigate,” says Captain Barr. “We’re relatively confident that a lot of what’s coming out of this region is making its way to New Zealand. There’s a good chance that heroin picked up at Auckland airport is originally from here.

“But we also go to the Middle East because doing so exposes you to other nations’ operations, activities, concerns and insights. In the Middle East, you see great power competition, crisis and conflict daily. You don’t see that kind of operating environment around New Zealand – for us it’s more about soft power projection, resource and border protection, and in-extremis responses to regional crises such as disaster response. Doing what we do in the Middle East, being exposed to the more traditional activities that militaries engage in, gets our people experienced in operations beyond disaster relief, so that if something of that nature happens near New Zealand, we’re better prepared.

“Don’t get me wrong, disaster relief is important, and one of the vital tasks we conduct in the Pacific, but it’s not the primary purpose of the military. It’s these preparations for conflict, and training for such, that enables us to switch rapidly to disaster response if needed.”

Even with limited resources, the Combined Maritime Forces is a great construct, he says.

“Countries have their own agendas, and their own bilateral relationships, but here in Bahrain everyone has to work together. You have Pakistan and India working in the same coalition, or Britain and Argentina, with the history they have! There’s a whole bunch of Gulf States working together for the safety and security of their region, which is just brilliant. And it’s growing.”

Commodore Ward sees it the same way.

“We have the home game and the away game. When we play the away game, we develop the skills to play and win the home game, in a Pacific Ocean that could get quite complicated. We’re growing the next generation of leaders, exposing them to the complexities of maritime security operations.

“Drug busts are awesome. But for me, there’s a lot of satisfaction in seeing our people learn, while working alongside India and other nations. We’ve demonstrated that, as a small nation, we can go to the other side of the world, and not just do something, but do it well, and that gets noticed.”