OP TIEKE

02 December, 2025

PREPARING CIVILIANS FOR THE FRONT LINES

Four large buses arrive at a military training centre, somewhere in the south of England.

Ukrainian men of mixed ages tentatively exit the bus. This isn’t a bunch of mates. None of them know each other. The overcast day does no favours to the surroundings, made up of barrack buildings, gravel plains, grassland, sections of woodland and rows of what look like abandoned terraced allotment buildings. The instructors can see the “where am I” looks on their faces.

Over 50 days, it’s the job of these instructors to give these Ukrainian trainees enough skills to be as well prepared for the front line as they can be. They will board a bus and start the trip back to Ukraine – and to the front line against Russia. It’s called Operation Interflex. New Zealand’s name for its contribution is Operation Tīeke.

Operation Tīeke

THREE YEARS IN

Since Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the NZDF has regularly deployed specialist teams to the United Kingdom as part of the international community’s support of Ukraine’s self-defence. Operation Interflex is British-led with partner nations of mainly NATO countries, with New Zealand and Australia also assisting Ukraine against Russia.

According to the UK Government, around 60,000 Ukrainian soldiers (as at June 2025) have been trained under this programme, which is designed to turn civilians into soldiers with battlefield essentials, capable of returning to Ukraine to fight against the Russian invasion. There’s no time for the formal side of being a soldier. There are no regimental aspects, no parade grounds. It’s about lethality, survivability and offensive spirit. In seven weeks a 50-year-old taxi driver or a 25-year-old factory worker will leave the facility and get placed on the front line in Ukraine.

The dynamic is unusual. Ukraine is fighting in Europe’s biggest land war since World War II, while the trainees are receiving instruction from countries who have never experienced the war they’ve come from. What countries like New Zealand bring is institutional credibility and experience. And in some cases it’s a two-way street, with Ukrainian battle experience influencing and adapting the instructors’ warfighting doctrine – which gets passed on to the next training intake.

Training soldiers that are going to be heading straight into a war environment, it's a very humbling experience as an instructor. We all know what's at stake for these guys, and you up your game to help them.

BASIC RECRUIT TRAINING

The training may be new for many of the trainees, but they are enthusiastic to learn, says New Zealand Army Instructor A.

“We’ve got such a short amount of time – these people are going straight into war as soon as they leave us, and most likely into life-or-death situations. So basically, we are taking a recruit training course and keeping all the fun bits – the exercises, the range time. We’re giving them the skills and knowledge to fight and win, in a very condensed period of time.”

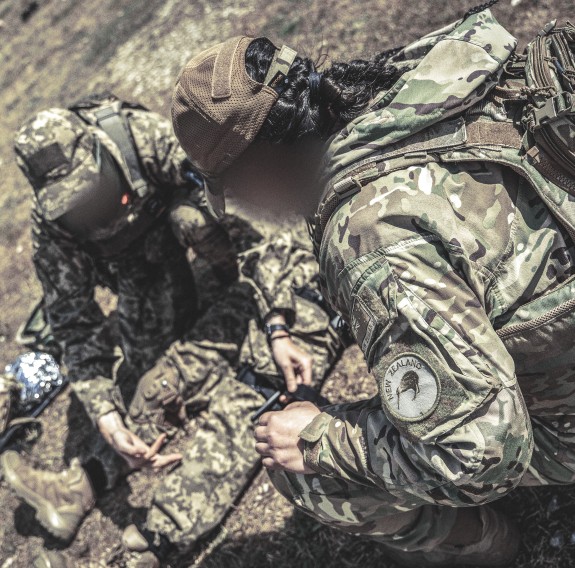

In the first two weeks, the instructors work with the trainees on individual skills - weapon handling, range shooting, medical training, counter-explosive, counter-drone and CBRN (Chemical Biological Radioactive Nuclear) training. Many have never touched a weapon before, so they need to be comfortable and confident with a rifle and look after it. Explain, Demonstrate, Imitate, Practise. ‘EDIP’ – over and over.

“They’ll look after that rifle better than any other bit of kit they have. At the end of the day, if it’s clean, it’s going to shoot, and if it’s going to shoot, it will save their life.”

The trainees move into the field, learning basic field hygiene and routine, creating shelters and looking after themselves and their comrades. Keeping concealed and applying camouflage paint to their faces are all new skills to take in. It’s a big thing, getting away from the comforts of barracks and learning to live in the bush, says Instructor A.

The first time in the bush, let alone handling a rifle, you can see that it’s overwhelming on some of them. You just need to take that step back and make sure you’re delivering training at a pace they can keep up with.

The trainees move on to exercises that have evolved to match the specific threats being faced on the frontlines in Ukraine.

“You see that they’re spending a lot of time in the trenches and in urban areas, so we dedicate a lot of time to train the students in trenches and in the urban, so they learn to fight and survive in those specific terrains.”

Training can’t be delivered in the same manner as training in New Zealand. Many of the Ukrainian trainees are conscripts, between 25 and 60 years old. A 25-year-old can throw themselves to the ground, roll, crawl and move in a hunched, low position. Some will even excel at the tasks. A man over 50, maybe fit, maybe not, is not going to be so blasé about that kind of movement.

“It’s not always go, go, go. There needs to be frequent rests. We want to make sure we deliver the training to the superstar, as well as the guy who might be dragging along, and levelling that training out to a happy medium.”

It’s a highlight for the instructors when they see the trainees gelling as a group and taking that next step into fighting in an urban environment. There would have been a time when the trainees would yell instructions to their comrades as they searched a house. They’d fire a round and crouch back down the stairway, not wanting to move. Now the soldiers progress through a house silently, using only hand signals and holding their mate’s shoulder to direct him.

“You can definitely see these guys have built confidence over the course, from the way they look after their rifles to their 2ICs checking on all their people. It’s not about them any more, it’s about the team.”

MEDICAL TRAINING

You notice he's still struggling to breathe? When you have a look at it, this side isn't rising, and this side is.

Not everyone in the war is trained as a medic. But as the war continues and casualties mount up, the Ukrainian soldiers are taught to care for their comrades until help arrives. On this kind of modern battlefield, that could take days.

It’s called Tactical Combat Casualty Care, or TCCC. The main aim is teaching the soldiers to identify and treat preventable causes of death to give as many people as possible a chance to survive on the battlefield.

“Yes, people die,” says Medical Instructor B. “It is a part of war and that is the sad reality. Common types of injury that are seen in the battlefield are what we call massive bleeds. Basically, a human being can bleed out in as little as three minutes.”

There are also blast injuries, from artillery or more commonly from enemy drones. The students are shown the kind of wound patterns that occur with blast injuries and how to handle them.

“The main types of training we teach are tourniquets, bandages, chest seals and hypothermia management – the main items we use on the battlefield in combat first aid.”

The tourniquet is one of the greatest medical devices a soldier has at their disposal, he says.

The instruction aims to provide realistic battlefield medical scenarios, featuring actors with blood-splattered, massive wounds and lost limbs.

"Seeing these wound patterns now will help desensitise them to the real ones they will find on the battlefield and this will help save lives because they will not freeze. You see some students that freeze for 30 seconds or more and during that time, the casualty is losing lots and lots of blood. The more blood you lose, the higher the chances of dying."

Casualty evacuation is something the trainees must consider. Traditionally armies have relied on helicopters to evacuate wounded soldiers. But in this war, a conventional military versus another conventional military, there’s the threat of drones.

“That means they are not likely to get a helicopter. So we have to teach them drags and carries, and using a drag stretcher on the battlefield.”

“Here, we’ve got about 200 students that we need to get through in a two-day period. A lot of them were civilians a few weeks ago and most of them knew nothing. They’ve got so much knowledge to take in, not just medicine but many aspects of military life.”

It is fulfilling to teach the soldiers to save lives on the battlefield, he says.

I teach them not to lose their humanity. Yes, there are evil people in this world, but that does not mean they need to be evil as well.

COUNTER-EXPLOSIVE

Counter Explosive Ordnance (CEO) Instructor C checks the fittings of gas masks on trainees as artificial smoke drifts across a flat gravel plain.

“Ideally, you want it on in less than 10 seconds,” he tells them. “If there’s a chemical attack, it probably means that enemy is about to attack you. So you should also be putting your helmet on.”

Ukraine is facing a sophisticated, superpower country. The trainees are going to face every aspect of modern conventional warfare, including mines, explosives and chemical and biological attacks – from an enemy with huge stockpiles.

Making up a Counter Explosive Ordnance team are New Zealand Army engineers. They’ve got a week for formalised training with the Ukrainians, but the engineers do their best to fit in more in and around other lessons.

CEO Instructor C appreciates that the Ukranians are getting “absolutely pumped” with information, but everything counts. These are skills the Ukrainians will be relying on to save their lives.

The instruction moves to the trenches where a trainee, relying on the instructions he’s received, uses two lengths of wire in each hand to probe in the dirt in front of him for buried mines.

He places markers either side, allowing his comrades to step carefully over the device.

A lot of what is being taught is based on insights and intelligence being passed on from Ukrainians who have been to the front. It’s forcing the engineers to constantly adapt.

“That flow of information means we can give up-to-date techniques that can help the average soldier survive,” he says.

There’s no point sticking to the manual.

Anything that can help the war effort, anything that can help these guys survive is incredibly important.

“Because they are adapting so fast, and then the enemy is adapting to counter it, you pretty much need to throw out the playbook in terms of doctrine and just give them adaptable drills.”

In such a fast-paced, changing war, Ukraine can’t afford any loss of momentum or consistency in the training, he says. If New Zealand pulled out, it would mean soldiers would receive different training while replacement engineers settled into the teaching. It would mean deaths that could have been avoided.

COUNTER-DRONE TECHNIQUES

A drone moves slowly and deliberately through a clearing. For the soldiers caught between open ground and the trees, do they seek cover and hope the operator doesn’t spot them? Or do they expose themselves and try and shoot it down?

It’s the new sound of warfare and a feature of the Russia-Ukraine war – the air-borne whine of the cheap, mass-produced drone. At the training centre, New Zealand Army Drone instructor D operates a drone that would not look out of place as a birthday present purchased for a youngster.

“This is something we haven’t seen before – the use of the cheap, commercially available drones on the modern battlefield,” he says.

“When Russia illegally invaded Ukraine and rolled in with tanks and expected it to be over in three days, they met something that they didn't anticipate - soldiers innovating with commercially available drones and showing how just something comparatively cheap could have a massive impact.

“You've got millions of dollars worth of armour and millions of dollars worth of aviation, and it's being shown up by a $6,000 drone. It's just something that we never thought we would see, and yet here it is.”

Drones are cheap and flyable by almost anyone with little or no training. They’re everywhere, and that means more casualties attributed to drones.

One of my roles here is every time they're doing another type of training we'll add drones into it. Sometimes, it’s just to observe them. Sometimes we’ll drop water bombs on them to simulate dropped grenades. It’s giving them that exposure over and over again to reinforce their learning.

The important thing is teaching them to make the split-second decision to either react to the drone or hide from it.

“For a drone, every second counts. You could be running from it, hiding from it, moving to a different bit of cover. In some cases, even shooting at it. The most important thing you can do to keep yourself safe is that the drone operator doesn’t see you.”

The instructor has just dropped a water balloon over soldiers lying on open ground. They roll away from the falling balloon, just as they’ve been trained, but some aren’t quick enough. He can see a couple of them are upset at being ‘got’ and walks over to talk to them.

“It’s better that you make that mistake here,” he tells them, “rather than in Ukraine on the zero line. Better you make the mistake when it’s me flying the drone, instead of a Russian soldier who is trying to kill you.”

Every repetition they do in training, even the ones where it goes wrong, is another repetition they would not have had if they had gone to the battlefield without training.

“You want to do the best job you can here with them. Sometimes it’s just the smallest little thing, like if you can get them to move away from the drone a couple of seconds faster, maybe they might stay alive just a little longer to stay in the fight.

“But it is hard. I know of soldiers that I've trained that have been killed in action. You sit there wondering if you did the best job you possibly could for them.”

Drone operations is an example of the “two-way street” learning, he says.

“We’ve got experienced soldiers here that we’re taking for other courses, and they are more than happy to teach us what they know about drones as well.

“So, we are also learning a lot ourselves. These are lessons that we can then take back to New Zealand and implement them into our own training and to keep ourselves as a relevant force for the 21st century.”

OPERATION INTERFLEX

Commanding Officer Training Delivery Unit 2, Lieutenant Colonel Rob Porter, British Army, counts themselves fortunate that New Zealand is among the six nations training Ukrainian soldiers.

“While this is UK-led and on UK soil, we are absolutely not doing this on our own. Operation Interflex could not have been achieved without the support of all the partner nations. Numbers are small from some countries, but their outputs are huge.”

He says the expertise New Zealand soldiers developed in training army soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan has been very useful for Interflex.

“There’s a lot of expertise in the New Zealand Army that’s done exactly what we’re looking to do here. Why would we not want the best people we can have to deliver this task? It’s fantastic to have such an experienced bunch of soldiers, very relaxed, very professional.”

It’s not about distance or geography – it’s about ethics, he says.

If you think that Ukrainians have a right to defend their homeland, then you’re absolutely right to be sending people over here to support and help out.

BACK TO THE FRONT

On departure day the New Zealand contingent farewell the Ukrainian trainees with the NZ Army haka. A Māori warrior escorts the loaded buses slowly past instructors from multiple countries, who stand on either side of the road, saluting their departing students.

Over 50 days, the instructors have gotten to know the soldiers well, the association heightened by the seriousness of what lies ahead for them.

Did we do enough? Did we do everything we could do? Could we have done better?

“They are very much like us,” says New Zealand Army Instructor E. “They come from all walks of life, which is the nature of a conscripted force.

“They have the same sense of humour, they have the same can-do attitude. They’re very family orientated. They just want their children to have a safe place to live and grown up. They’re just fighting for the right to exist.

“If I can just keep one of them alive to come home to his family, or I can keep him alive a little bit longer so that he can fight off his enemies a little bit longer so that someone else can go home to their family, that’s what motivates me.”

Go behind the wire, watch our exclusive Op Tīeke video series.